About

Cardboard Camp:

Stories of Sudanese Refugees in Lebanon

Authors: Maja Janmyr & Yazan Al-Saadi

Foreword: K, a Sudanese refugee in Lebanon

Art Director and Illustrator of Act 2: Omar Khouri

Illustrator of Fahima’s story Act 1 and 3: Noemie Honein

Illustrator of Sultan’s story Act 1 and 3: Anthony Hanna

Illustrator of Kudi’s story Act 1 and 3: Sirène Moukheiber

Copy Editing: Chloé Benoist

Arabic Translation: Wini Omer

Graphic Designer: Farah Fayyad

Web Developer: Layal Khatib

Foreword:

I know about something called human rights. Me, as a person, I have human rights. I will hold on to my rights, I will not waiver. That is the first thing I want to say.

For me, this book is evidence. It is proof our stories exist and a reminder that together we are strong, despite our struggles. I read a lot about refugees, the refugee status, and the Geneva Convention of 1951. I know that we have rights, these rights exist in the UN (United Nations), and that you have to take them. Accordingly, we tried several times to do that – to get our rights in a peaceful way one by one. But the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) refused us, so we resorted to the sit-in. We gathered.

Maybe one day the UNHCR’s heart will open for those who were at the sit-in. I still think about how to reach out to the UNHCR, and others, to make them understand. I’ve been here since 2002. If I’m talking with people back home who are telling me about the situation there, how can I go back? I can’t go back, and I have a child and a wife, should I leave them? Should I leave when I don’t know where my whole family is? How can I leave?

And why am I staying here in Lebanon? Because I’m already a refugee. I know that there aren’t many Sudanese refugees who can go to another country, unlike other refugees in Lebanon. We only want equality and justice. There’s no equality, no justice. We wonder why other refugees can leave while we stay and wait for resettlement for many, many years.

People from the UNHCR resettlement unit say: “Resettlement is a solution, not a right.” I tell them: “Okay I want the solution. Let’s focus on the solution.” I tell them: “Let’s talk about the solutions, what are the solutions?” Yet, I do not find answers.

Our life in Lebanon is a struggle from morning to night. This book brings color to our struggles. This way, we hope that the people of Lebanon, people of the world, will not forget us. They will understand us. They will understand why we cannot go back to Sudan and why we cannot stay in Lebanon.

K, a Sudanese refugee in Lebanon.

Preface:

One January afternoon on a sidewalk across from the Beirut office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), I joined as a researcher a group of Sudanese protection seekers who have camped there for over seven months. To escape the wind and rain, we huddle close together on sheets of cardboard, a plastic tarp above our heads. We’ve taken our shoes off to keep the cardboard clean and dry, and we watch videos of the storm that had pummeled their protest camp the previous night. We talk – about the past, present and future, about hopes and dreams.

Lebanon has long been a destination for persecuted Sudanese who seek access to the protection, aid, and resettlement services of UNHCR. Once here, however, they have many reasons for seeking to influence UNHCR’s provision of protection and assistance. Their situation has continuously been overshadowed by humanitarian emergency responses targeting refugee groups deemed to have greater political interest. A recent vulnerability assessment by UNHCR itself among others highlighted how Sudanese refugees in Lebanon are among those who are “systematically worse off [than other refugee groups], and at times significantly so, for virtually all indicators”.1 Unable to meet the requirements needed to obtain Lebanese residency permits, most reside irregularly in the country and are vulnerable to arbitrary arrest, detention, and deportation to Sudan.

There is a temporality, informality, and fragility of cardboard that bears a resemblance to the opportunities for refugee civic engagement in Beirut. As politically disenfranchised non-citizens, refugees are not expected to be politically vocal during their exile.2 Yet, across the globe, refugees and asylum seekers have sought to challenge the power relations embedded within the international refugee regime. Sudanese protection seekers in Lebanon are no different, aspiring to defy ingrained inequalities within the broader humanitarian system – inequalities that, in the Lebanese context, are also aggravated by the longstanding and intertwined dynamics of Arab nationalism, colonial histories, and racism. Sudanese protection seekers in Beirut have not remained “silent objects”3 and have loudly pushed for agendas defined by, and for, themselves.

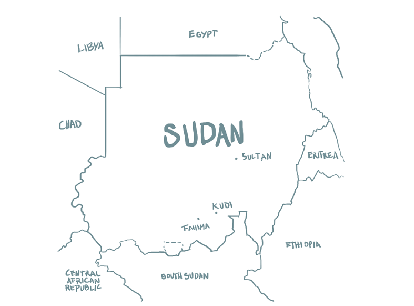

You are now about to read a story inspired by their perspectives. While the characters and events are fictional, the depictions of life as a refugee protester draw on extensive ethnographic research carried out with Sudanese protection seekers in Beirut between 2015 and 2021. Their needs, aspirations, and concerns are complex and multifaceted, and it is impossible to fully do justice to their experiences. We hope to spotlight some of their daily concerns and struggles, and to remember that such struggles persist alongside and within larger humanitarian governance systems, in Lebanon and beyond.

Maja Janmyr

This publication is developed as part of the REF-ARAB project at the University of Oslo, funded by the Research Council of Norway’s independent projects (FRIPRO) programme, grant number 286745. The content of the publication is the sole responsibility of the creators behind this comic.

You are Free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material

The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

- ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices:

- You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation.

- No warranties are given. The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material.